This piece may be too long for email inboxes, so you might have to click the title to read it in your browser—sorry about that!

The Event

On October 10, 2024, electric vehicle company Tesla held an event to unveil a new product: an autonomous two-seater car, pitched as a robotaxi—the Cybercab—that ostensibly represents the company’s vision for the future.

Some humanoid robots were also presented, and another vehicle, dubbed the Robovan, was also on display.

Though some people thought the whole undertaking was pretty neat (in an Epcot-like, “here’s a whizbang look at the future” sense), the general consensus is that this event was a letdown, was maybe an elaborate distraction, and/or it was an indication that the company’s leadership is scrambling to justify Tesla’s sky-high valuation at a moment in which its future has never been more threatened and in question.

The CEO

Before we jump into the company’s plans and presentation (and that response to the event), though, it’s important to note that getting a read on any company owned and CEO’d by Elon Musk is a tricky business; it always has been to some degree, but it’s even more the case now as he’s recently become incredibly political, increasingly vocal about his politics, and by some measures the “most divorced man ever” (a criticism that gestures at his seemingly frantic shouts for attention and bizarre decisions—though he’s pretty divorced in a literal sense, too).

Musk is also a well-known fantasist: a trait that’s often celebrated in would-be visionary leaders, but which can also lead to a fixation on unattainable deadlines and dreams. And while he’s been involved with some things that (I would argue) are undeniably groundbreaking and historic (at times against all odds), he’s also repeatedly made predictions that didn’t come true, made claims seemingly for the purposes of increasing the stock price of his companies, and (also seemingly) knowingly outright lied in order to portray business environments (and technological realities) in manners that suited his needs.

(He’s also been massively red-pilled over the past handful of years, so no matter what he says or does, there will be a significant number of people who assume he’s confabulating or doing things with ill-intent—fairly or unfairly.)

So Musk’s words aren’t always best taken at face-value, he consistently makes promises (especially about deadlines and milestones) that he later backtracks on, and he’s doing a lot of bizarre (purportedly drug-influenced) things, which tarnishes his credibility a bit (including, apparently, staying in touch with Russian President Putin).

Back to the Event

That in mind, Musk introduced the Cybercab and Robovan at this recent event, alongside a humanoid robot (called Optimus, though sometimes called the Tesla Bot) at a Hollywood backlot.

The intention was to show off the company’s next step plans, which are oriented around automation and changing the automobile paradigm so that folks no longer have to drive (these vehicles don’t even have a steering wheel) and can instead rely upon Tesla software to haul them from place to place.

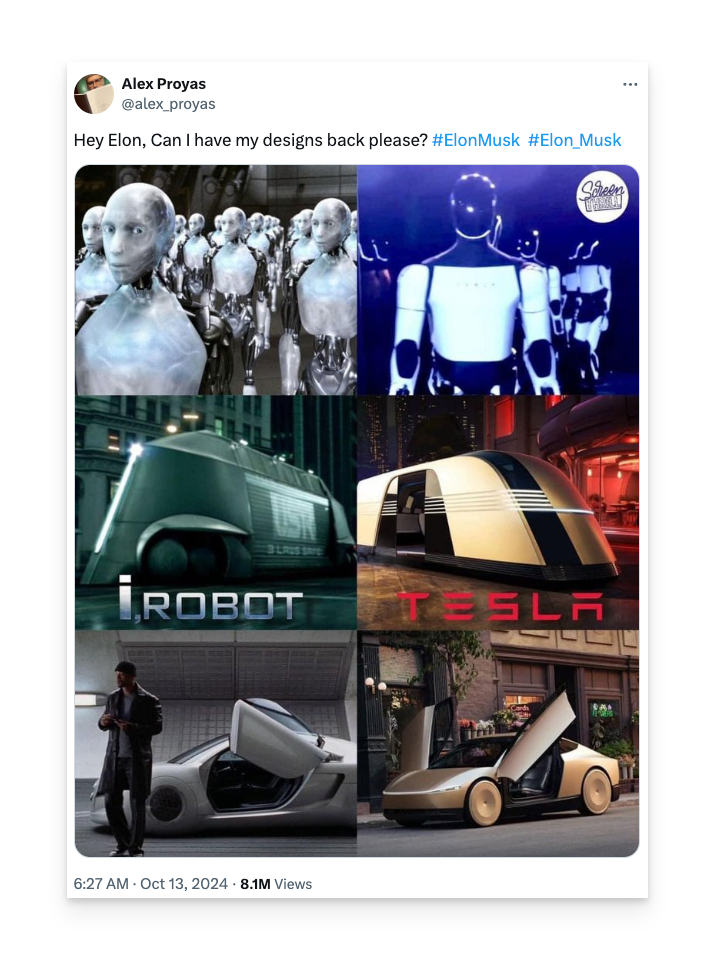

The two new vehicles seem to borrow a lot of their design language from the 2004 film, I Robot (the Optimus robots look similar to the emergently intelligent bots in that film, as well), and the folks behind the new Bladerunner movie are apparently suing because Tesla decided to use AI to generate imagery similar to imagery from the film, after they declined to give the company permission to use actual film footage.

Musk said that these vehicles would be fully self-driving (FSD), would cost 20 cents-per-mile to operate, and would eventually be purchasable for just $30,000 apiece: a price-point that would allow individuals to buy their own robotaxis to rent out (for profit) when they’re not being used.

He also say that the company expects to begin operation of completely unsupervised, FSD in existing Tesla vehicles in California and Texas (on public roads) in 2025, and that the Cybercab should be on roads before 2027 (a recent independent evaluation into Tesla’s FSD found that it required human intervention every 13 miles or so, however, which makes this timeline seem quite optimistic).

The Cybercab is a small, two-seat car that looks a bit like a DeLorean, and which has a lot of leg room and minimalist design elements.

The Robovan is a bullet-shaped vehicle with no visible wheels that can purportedly carry up to 20 people, the interior rearrangeable for a variety of use-cases.

The Optimus robot was partly pitched as an automatic means of cleaning these vehicles, but they’ve also been promoted as sleepless, omni-capable servants

All of which is pretty interesting and very sci-fi!

But! And this is a big but:

The vehicles shown at the event drove themselves slowly through a well-mapped backlot, not on actual streets (other companies are driving small autonomous vehicles on real-deal streets, and Chinese companies have deployed autonomous buses in big cities).

The Optimus robots were controlled by human beings, remotely, not by fancy AI.

This event, though interesting and compelling by some measures—especially for what it seemed to suggest about the near-future potential of transportation—was nonetheless super-not-real.

That competitive reality, combined with Musk’s abundance of dreams, but near-complete lack of numbers, hard deadlines, and plans for new conventional EV models led to a significant drop in Tesla share prices that stayed low for a while, only recovering over the past few days on estimate-beating earnings news.

The Promise

Something I personally think that Musk got right at this event, despite all the stagecraft and lack of business-world red meat, is the general promise of autonomous vehicles.

One of the core arguments for developing and deploying this collection of technologies, on scale, is that humans are fallible, we drink and drive, we get distracted by our phones and tired when we’re bored or haven’t gotten enough sleep, and that means a lot of accidents that didn’t need to happen (which in turn means a lot of property destruction, injuries, and deaths that maybe could have been prevented).

If we could replace drunk, sleepy humans with immortal, perpetually aware software optimized for this purpose, then, we might be able to substantially reduce the incidence and impact of such accidents.

The exact numbers vary from company to company (and have varied over the years as their vehicles and software have gotten better), but almost every autonomous vehicle type has a better safety record than average human drivers (in some cases substantially better).

That said, it’s scarier to think about robo-vehicles plowing into us (or plowing us into someone else’s car, their body, or their dog), so the standards for safety are artificially higher for autonomous vehicles than human-driven ones (anything other than perfection or near-perfection is basically a non-starter because of this status quo bias).

Doing away with human drivers would also (ostensibly, at least) dramatically cut the cost of operating for-profit vehicles (taxis, long-haul cargo trucks, Amazon delivery vans, etc) while also freeing up gobs of time commuters would otherwise have to spend staring at the road.

The long-term potential of getting this right, then, is that cars and other vehicles could be redesigned entirely, becoming mobile rooms filled with TVs and games, gym equipment, portable offices, beds, couches, or maybe modular setups that can be rearranged based on the needs and preferences of the owner or user.

In order to make that a reality, though, we have to do away with the human driver, and we have to remove human-driver-oriented things like the steering wheel, rearview mirror, and the gas and brake pedals.

Most present-day semi-autonomous vehicles have tech that basically offers fancy cruise control: the driver required to keep their eyes forward and hands on the wheel (in some cases forced to do so by software that tracks their movements), while the more fully autonomous systems of today either still have the basics (pedals, steering wheel, etc) so that a human driver can take over if necessary, or in some cases those elements have been offshored, remote workers able to (wirelessly) pop in and take control if the autonomous software encounters something it can’t handle or doesn’t understand.

If these technologies could be iterated to the point that the human element is safely removed, though, the software and hardware so good and capable that it’s actually more dangerous to have a human driver in control, that would theoretically lead to a lot of new transportation possibilities, upending the car and travel industry in the process.

The Technology

A couple of points on the tech side of things before we jump back into the reality of autonomous vehicles as they exist, today.

First, this collection of technologies have been in the works since at least the early 20th century (initial investments by all sorts of entities leading to things like cruise control by mid-century), and progress has been decently steady in the decades since.

DARPA started developing these sorts of technologies back in the 1980s, and it was able to get one of its vehicles (a minivan called the NavLab 5) across the width of the US (from Pittsburg to San Diego), fully autonomous 98.2% of the time and at an average speed of 63.8 mph, in 1995.

The agency then held a “DARPA Grand Challenge” in 2004, offering a million-dollar prize to any team that could build an autonomous vehicle capable of traversing a 105-mile course they built in the Mojave Desert; the “winning” team made it just 7.32 miles, so no money was awarded.

The second Grand Challenge went much better, though, with five vehicles completing the 132-mile course (which included narrow tunnels and a lot of sharp turns).

By 2015, five states and Washington DC were allowing autonomous car testing on public roads, and an autonomous hatchback traveled about 3,400 miles across the US, doing 99% of the driving without human input; quite a leap, considering that this was accomplished by a private company a mere 11-years after all those failures at the first Grand Challenge event.

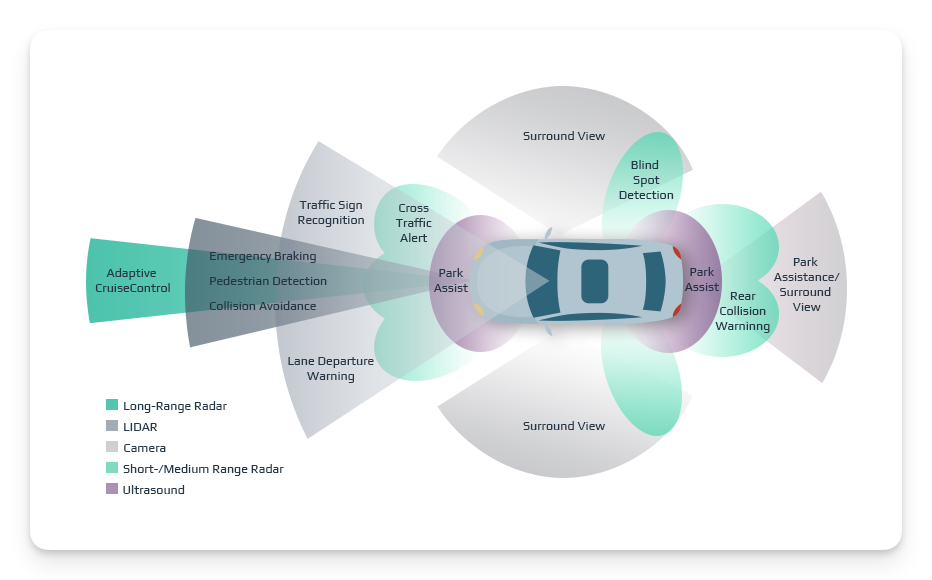

Second, there isn’t a universally agreed-upon bundle of tech for autonomous vehicles, but the sensor cluster is becoming more standardized as companies reinvest in what’s working for them, their use-cases, and their vehicles; most of them have landed on some combination of LiDAR, cameras, and radar, with some companies using ultrasound, as well.

A sparse few, most notably Tesla, have opted to focus entirely or almost entirely on camera-collected visuals rather than environmental info from those other types of sensors.

The idea seems to be based on a strategy of avoiding high costs (and periodic shortages) associated with LiDAR hardware and installing different sorts of sensors (and computing the data all those sensors collect) around a vehicle, and then using high-end AI to parse the visuals from upgraded cameras that cover more ground than typical autonomous vehicle cameras.

This means Tesla only has a single data type they have to work with, and that should (in theory) help them evolve their Tesla Vision autopilot system faster (and hopefully better), compared to their multi-data-type rivals.

There’s a lot of risk in this sort of strategy, and again, most other notables in this space are still using (in most cases) a trio of sensor types so that, for instance, when it’s super-dark outside, LiDAR will still have an essentially unimpeded view, while ultrasound works well in all sorts of weather conditions and benefits from a bunch of sensors all over the vehicle because they’re inexpensive to buy and install compared to other sensor types.

Each company also has their own software suite which is trained on (usually something like) billions of miles of real-world and simulated driving, and they aggregate all that experience so every vehicle can use their sensors better, over time.

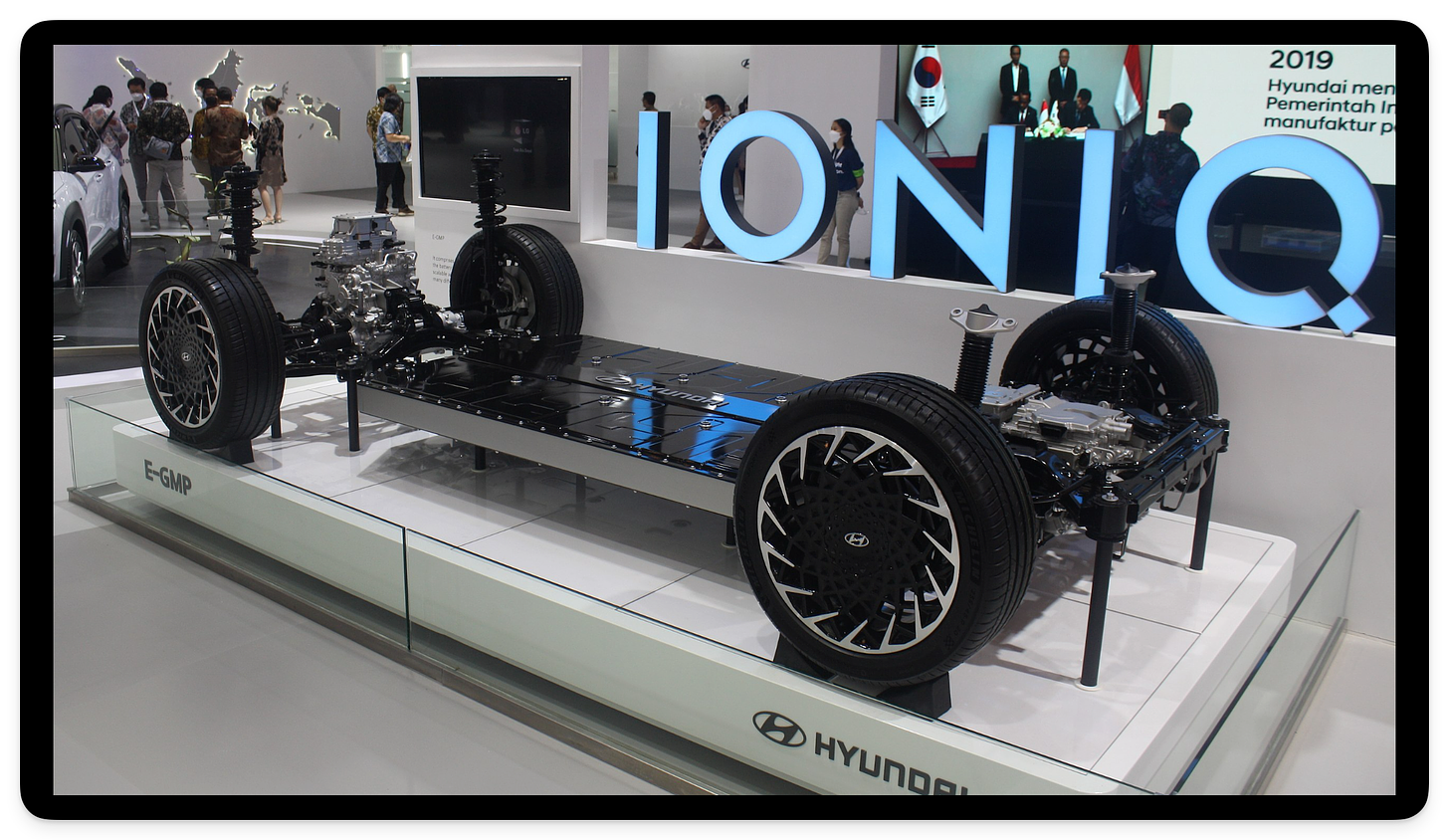

And third, most autonomous vehicles are also electric vehicles because it’s a lot easier to keep all that sensory information, computation, and the actual control over the vehicle’s movement electric and electromechanical.

It’s just simpler to keep things electric, top to bottom, basically, and that’s true of the car’s movement and other functionality, but also its updates, which can usually then be delivered over-the-air (OTA) like a smartphone update, rather than the vehicle having to be brought in to a dealer.

It’s simpler to fill up a car’s battery (in some cases wirelessly) than to fill up a gas tank, and having fewer moving (and chemical-exposed) parts means fewer things that will regularly break and more potential for mass-production of components (like, for instance, incorporating the whole of the car’s functional parts into a “skateboard,” and simply installing different tops to build different models).

So it tends to be assumed that modern autonomous vehicles will also be electric vehicles, because there’s a lot of crossover in the tech, because EVs are generally considered to be the future (in terms of cost, performance, further optimizability, etc), and because many of the companies investing in autonomous vehicles are also keen to build clean, green, networked fleets of these things, and the “clean, green” part requires that they’re powered by renewables.

Levels

While we’re talking about hardware, let’s touch real quick on the ranking system that’s used by regulators to identity how autonomous these vehicles are capable of being (and are allowed to be), which takes said tech into consideration.

The ranking system is as such:

No autonomy features.

Simple driver-assist features, like help controlling speed (“cruise control”) or keeping the steering wheel steady (the driver must stay aware and in control of pretty much everything, though).

Similar driver-assist features, but with a little more autonomy on the car’s part, and while the driver still has to pay attention to what’s going on and stay in control, the car can do a fair amount of the driving on its own.

This level is called “Conditional Driving Automation,” and the general idea is that while the driver must still be in the driver’s seat and ready to take over if necessary, the car can usually drive (and park) itself when asked to do so.

This is similar to Level 3, but with the addition of sophisticated software that allows the vehicle to navigate complex issues without the driver’s assistance, so it doesn’t require a human being sitting in a driver’s seat and ready to take over to function.

This is the goal many of these companies are aiming for with their autonomous systems: the car drives itself, navigates tricky stuff itself, doesn’t need humans aboard to function and do things, and would basically allow passengers to sleep or work or do whatever else they like because the car’s got everything handled.

(The main difference between Levels 4 and 5 is that vehicles in the former category can handle most, but not quite everything, and are thus typically relegated to simple routes in low-speed areas, while vehicles in the latter category should theoretically be able to putter around forever, accomplishing all speeds and all tasks with the same or better skill as a human driver.)

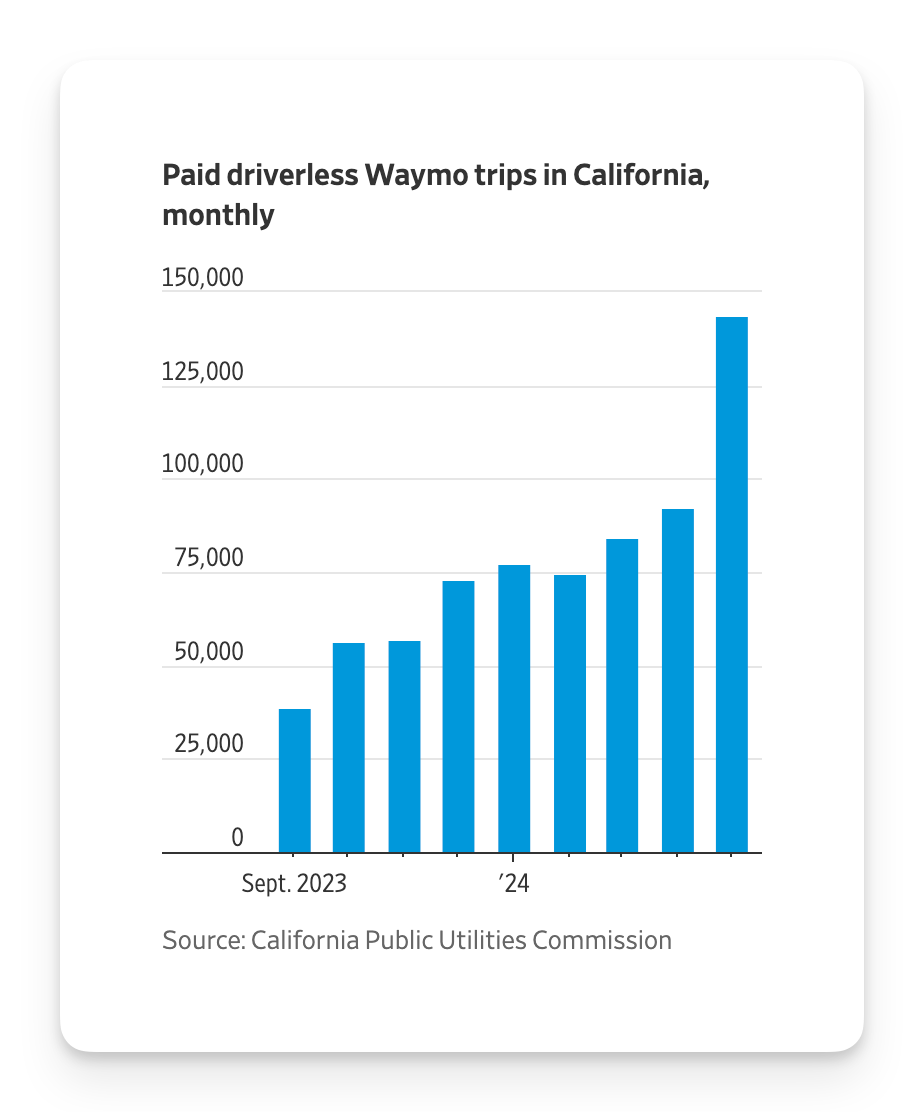

The newly announced Cybercab and Robovan are purported (by Tesla) to be Level 4 vehicles, and Waymo was the first company to offer (in 2020) Level 4 taxi services in a very few, limited areas (though that operating range has expanded substantially over the past few years, mostly in the US southwest).

Several companies in China (including but not limited to tech-giant Baidu) are operating hundreds of Level 4 vehicles around the country, even on major city streets, and are beginning to expand beyond China, as well).

The Situation Today

So the autonomous vehicle market (which includes vehicles that offer driver-assist technologies, levels 1-4) looks to be around $41 billion in 2024, and that figure is expected to keep increasing as the simpler (and less risky) versions of autonomy make their way into essentially every newly produced vehicle (especially EVs, not but exclusively EVs).

A bunch of those newer vehicles have Level 3 autonomy built-in already, though, so the major difference we’re looking at, between what’s increasingly widely available and what’s not yet ready for prime time is the ability for drivers to no longer be responsible for keeping tabs on the driving situation, ready to step in when necessary.

The next step after that is allowing folks to travel without worrying about the drive at all, essentially being transported in a room with wheels, no need for steering apparatuses or pedals of any kind (and no real need for antiquated inclusions like windshields, if the passengers want to watch a movie or sleep for the duration of their trip and light from outside would impede that ambition).

Tesla’s semi-autonomous capabilities (Autopilot) are broadly distributed across their vehicles, but also have a somewhat grim record, and the company is under investigation by federal regulators for a handful of crashes that occurred while the car was handling most of the driving in less-than-ideal optical conditions.

Tesla’s gambit with these new vehicles, then, could be seen as an effort to carve out space in that next-step corner of the industry, despite (by many indications) not quite being there yet.

They’re showing what’s next to keep investors and customers excited—but even if Tesla’s (alleged) “autonowashing” efforts are successful and earn them some leeway in some regions, it’s unlikely they’ll be able to deploy these things to their full capacity right away, except in very limited places and cases; regulations are just too strict to allow much real-world experimentation, at the moment.

Regulations on autonomous vehicles vary substantially from country to country, but the Department of Transportation (which decides the foundations of these regulations in the US) is pretty strict on what can be sold and driven where.

States have been making some of their own local regulations in recent years, and that’s why we see a lot more autonomous vehicles on the road in places like California and Arizona, where the rules are a bit more loose, while other parts of the country are either more locked-down or less well-defined in this regard.

China’s local companies are also on a fairly tight leash, but their government has recently decided to open up more territory for experimentation and development, possibly as part of a larger move to get ahead in this space and own the global autonomous vehicle industry in the same way they’ve basically conquered the global EV industry.

These regulations are so heavy, in part, because there have been numerous deaths caused by autonomous vehicles; most of those deaths were attributable to Level 2 vehicles—the human driver assuming the car would handle a situation it couldn’t handle, maybe, or not paying sufficient attention while the autonomous systems were activated—but some have been connected to Level 3 and 4 vehicles, as well.

As I mentioned before, though, despite these numbers still being pretty favorable in terms of deaths, injuries, and overall accidents (compared to cars with human drivers), new technologies typically have higher hurdles to leap compared to status quo ones.

So it’s not enough to just do a bit better than humans when it comes to car accidents because we’ve internalized the risk of being hit (and maybe even killed) by a human in a car, but a robot-driven car? That’s extra terrifying and basically unacceptable.

How We Might Think About All This

A somewhat concise way of thinking about the autonomous vehicle space right now is that Waymo (and to a somewhat lesser degree, Cruise) is killing it in the States, a handful of companies are killing it (for a scaled-up version of “killing it”) in China, and Tesla is promoting a next-step version of what these other companies are already doing, but without having shown they can accomplish that next step (or providing any hard deadlines or numbers to indicate when they will provide such evidence).

Also, Tesla’s robots seem less capable than others on the market, and they seem to be a fair bit behind their chief car rivals, as well: their main differentiator being the look of their products (which seem to have in some cases been stolen from sci-fi movies that were produced to serve as a warning, not as a “please build this future, it’ll be great” sort of message).

All that said, Musk’s companies (and the people who work for them) have repeatedly defied expectations: Tesla basically created the modern electric vehicle market and SpaceX fundamentally changed the economics of the space launch industry.

These are not small feats, and they weren’t accomplished by toeing the line; they arguably required a lot of investment of time and money, and a strong sense that those running these companies (including Musk) know better than every other person and business entity (and regulatory body) in their industry.

Also—and this seems like a small thing but it’s not—Tesla will benefit from economies of scale with their autonomous vehicles from day one, while the Waymos of the world are spending huge sums of money to buy appropriate vehicles and then even more money to upfit them so they can be used autonomously.

Tesla is developing both software and hardware in tandem, and already has the physical infrastructure to manufacture their own vehicles—which is an advantage some Chinese companies in this space have, as well. But even Cruise (which is a subsidiary of GM) doesn’t enjoy that same hand-in-glove software-hardware dynamic, which could also prove to be a competitive advantage.

Finally, Tesla already has millions of vehicles on the road, and all the models they’ve shipped since 2019 are (ostensibly, at least) FSD-capable, and thus (ostensibly?) capable of full- or near-autonomy.

And all of this is true however we might feel about Musk himself, his politics, and/or his bomb-throwing approach to regulations (and abundant fabrications and lies).

It’s also true, though, that while Tesla seems to be trying to create their own omni-service, complete with autonomous robotaxis and robots to clean them, Uber already has a version of this going and is rapidly incorporating other companies’ vehicles into their offerings (including Teslas, which are apparently causing some trouble because of how they’re being used by some drivers).

That means we’re seeing the Waymos of the world partnering up with entities like Uber, getting more of these things out on streets so that edge-cases can be noted and handled (which is arguably the main problem most companies in this space are struggling with right now).

Tesla recently divulged that they’ve been running an internal robotaxi service (just for Tesla employees, complete with an Uber-like app and just-in-case safety drivers), but there’s a big difference between running a regulatorily approved actual business and a small, employee-only project that doesn’t need to earn revenue or adhere to the full array of public-facing legal requirements.

Tesla benefits from all the data collected as their customers drive their vehicles around in real-world conditions, but the experience these other companies are getting with automated taxi services (including how to run the platforms underpinning the business of such a service) is another element of this industry that Tesla would seem to be behind on, which is important because the economics of robotaxi fleets aren’t inherently better than those of human-driven taxis.

Over the next several years, then, we’ll probably continue to see the slow roll-out of truly autonomous vehicle networks on a city-by-city basis (mostly in weather- and landscape-friendly areas to start), and we’ll see a lot of razzly-dazzly claims beyond that, too.

But unless there’s some kind of breakthrough by Tesla or another interested party, we’re likely looking at an iterative process of solving those lingering edge-case issues, rather than an easy to claim, harder to make actually happen, revolutionary one.

Thanks for reading! Please share your hellos, insights, counterpoints, and feedback in the comments or via email.

For purely selfish reasons, my dream is to be able to ditch my TWO cars and simply press a button on an app to have a small pod come to my house and carry me off (even if slowly). I could read or do a bit of work and arrive calm and unstressed by traffic.

Do we know wich cities are most aggressively moving toward this future?